At its inception, photography became an essential yet passive witness to life in society, to family, and to the events that mark life’s journey. Gradually, it broke free from this primary function to venture out into the world, capturing different civilizations and offering a more personal perspective. Photography began to raise public awareness of distant territories or little-known populations, with a desire to inform and even to alert. This approach emerged in the work of several photographers.

Photography as a simple witness then transformed into a manifesto, a spokesperson with the power to shift consciousness, inspire foundational actions, commitments, and even laws. Activist photography was born, aiming to eliminate ignorance as an excuse. It embraced major societal themes and played a crucial role in portraying poverty, making visible a reality often overlooked or misunderstood.

The pioneers of this tool for raising awareness

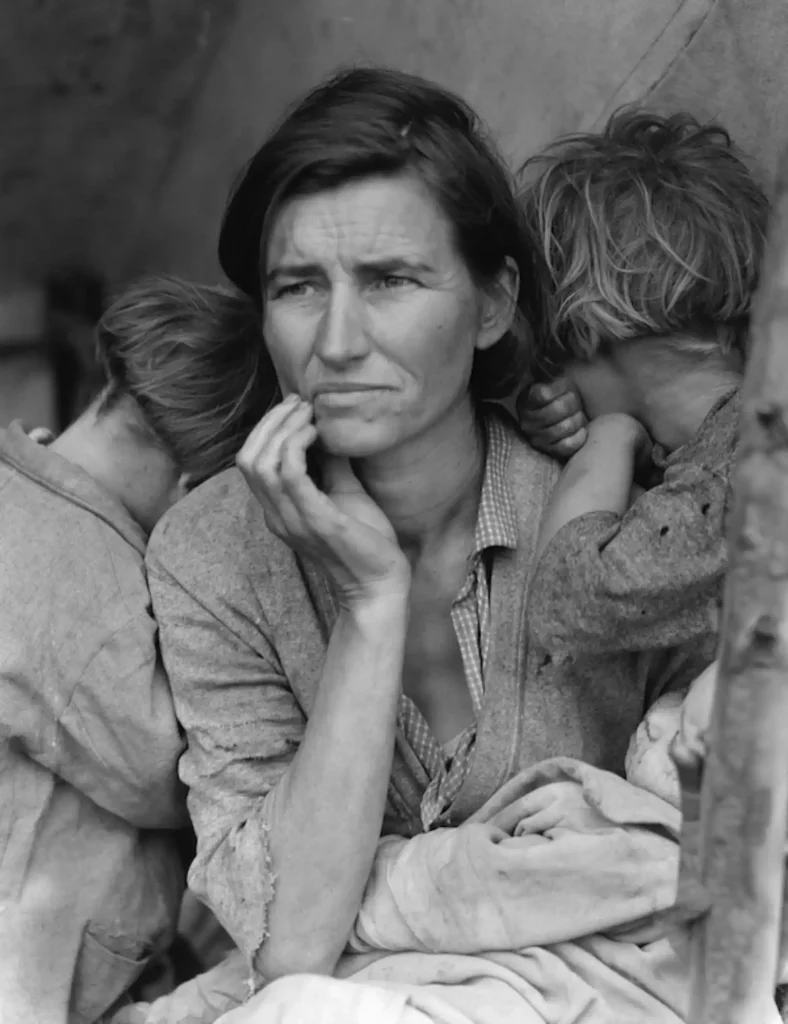

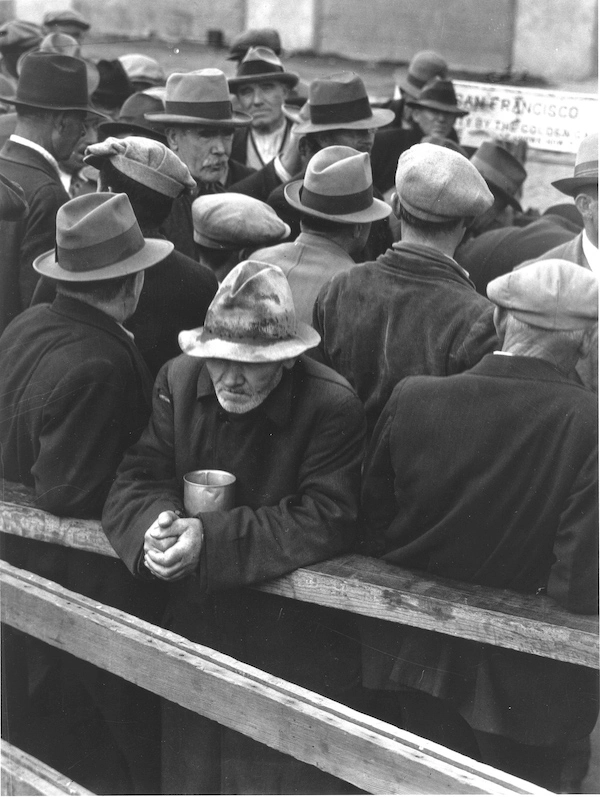

The photography of these pioneers provided a direct glimpse into the lives of people experiencing poverty. It shed light, in particular, on the Great Depression, a major event in the early 20th century in the United States, which left entire families homeless.

How can one not recall the work of photographer Dorothea Lange with her image Migrant Mother? This striking black-and-white portrait captures a woman, worn down by hardship, with a weary, anxious gaze, framed by the childlike figures nestled against her shoulders—a symbolic representation of this American financial crisis. Dorothea Lange managed to encapsulate, in a single image, the living conditions, emotions, and dignity of those struck so brutally by poverty. This photo series was commissioned by the Farm Security Administration (FSA), which aimed to publish a book on the devastation caused by this severe crisis.

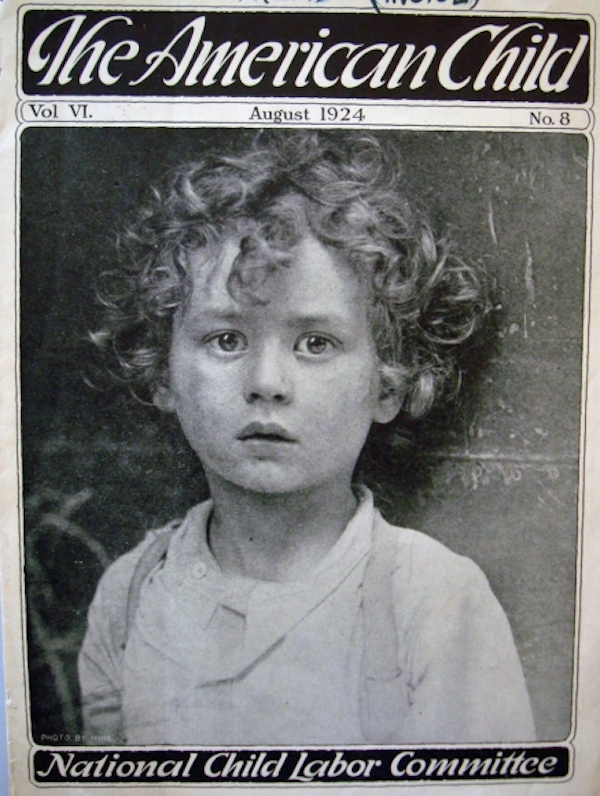

Lewis Hine, a sociologist and photographer born in the late 19th century, was one of the first to confront labor conditions, particularly child labor in factories, in collaboration with the National Child Labor Committee, which fought against the employment of children in heavy industry.

For Hine, photography was proof. He traveled through cotton mills, factories, and mines with his camera, capturing scenes he found intolerable. Through photography—far more impactful than his sociological work alone—he exposed the daily lives of these children, sharing it widely across American society. Hine mastered his tool as a means of effective advocacy, framing shots at face level and positioning the children against the backdrop of the oversized machines. His images conveyed his vision powerfully, aiming to raise awareness and evoke empathy in viewers.

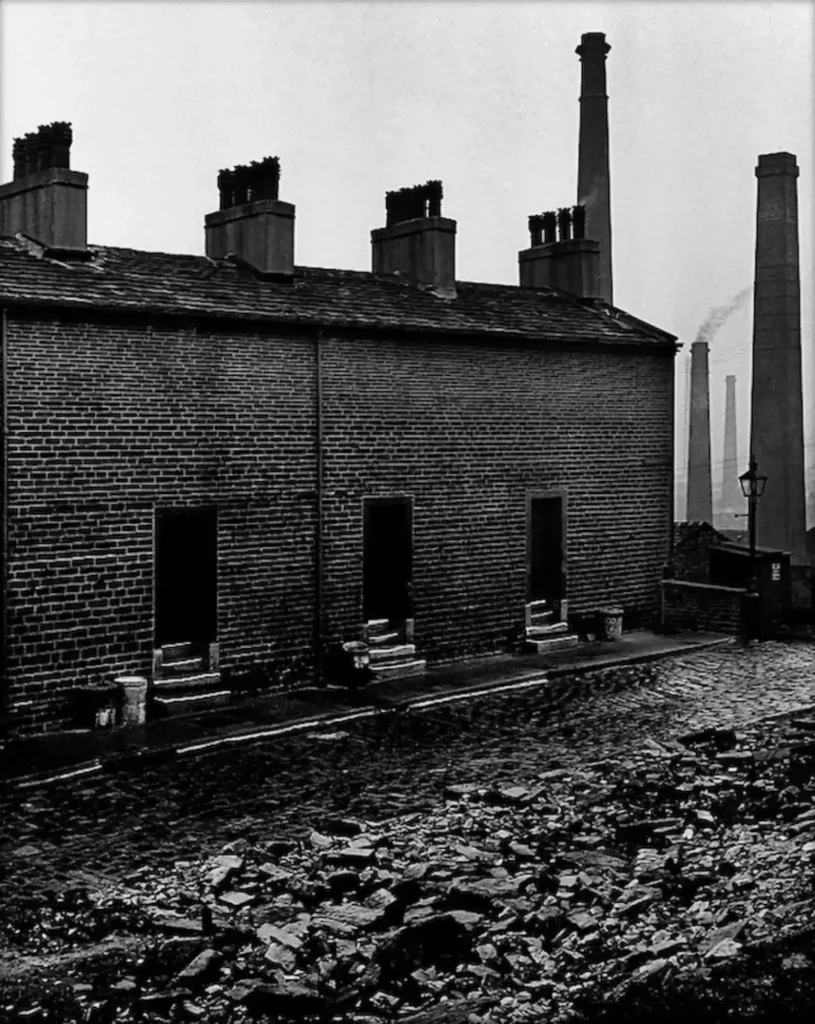

Following in this path, Bill Brandt turned his lens in 1926 toward the coal miners of northern England. His photographic signature is marked by intentionally high-contrast images, with deep blacks that underscore the tragic existence of the miners.

Images as the voice of the forgotten

This demonstrates that the meaningful power of photography is far from negligible. It is a massive instrument of influence. Photographs can be true catalysts, capable of shaping judgments, fostering a heightened awareness of critical issues, and pushing those in power to reflect beyond technocratic boundaries. They motivate actions toward greater social justice.

In 1940, Gordon Parks became the first African American photographer to reveal and publicize the social injustices faced by his community. Poverty, inequality, and racism—his camera bore witness to these issues, ensuring they would not be forgotten. His remarkable work for the Farm Security Administration helped to underscore the need for social justice. “I chose my camera as a weapon against everything I dislike about America: poverty, racism, discrimination,” he said.

A reality in full view

Sixty years after Lewis Hine’s work, Sebastião Salgado’s photographs from the heart of the Sierra Pelada gold mine in Brazil examine humanity’s relationship with profit and the thin line between human dignity and brutality. His work raises the question: has the world truly changed in half a century?

Mary Ellen Mark is an American photographer who has focused on the fate of marginalized people, individuals and families living in poverty in the United States. She offers a vivid reading of the daily struggles of homeless people, street children and struggling families. Streetwise is a photographic series that follows homeless children in Seattle, and in particular Tiny, a 13-year-old prostitute, whom she reunited with years later.

Steve McCurry is known for his famous portrait of the young Afghan girl with green eyes, published in National Geographic. The Middle East and Asia are his areas of focus. Conflicts, war, and poverty—his frequent subjects—form a tragic trilogy he often explores.

His images are colorful and aesthetically refined, sometimes in contrast with the violence of the subjects depicted. Through his work, McCurry aims to honor the resilience of the affected populations. The choice of beauty and light in his images is closely tied to this focus on survival and endurance.

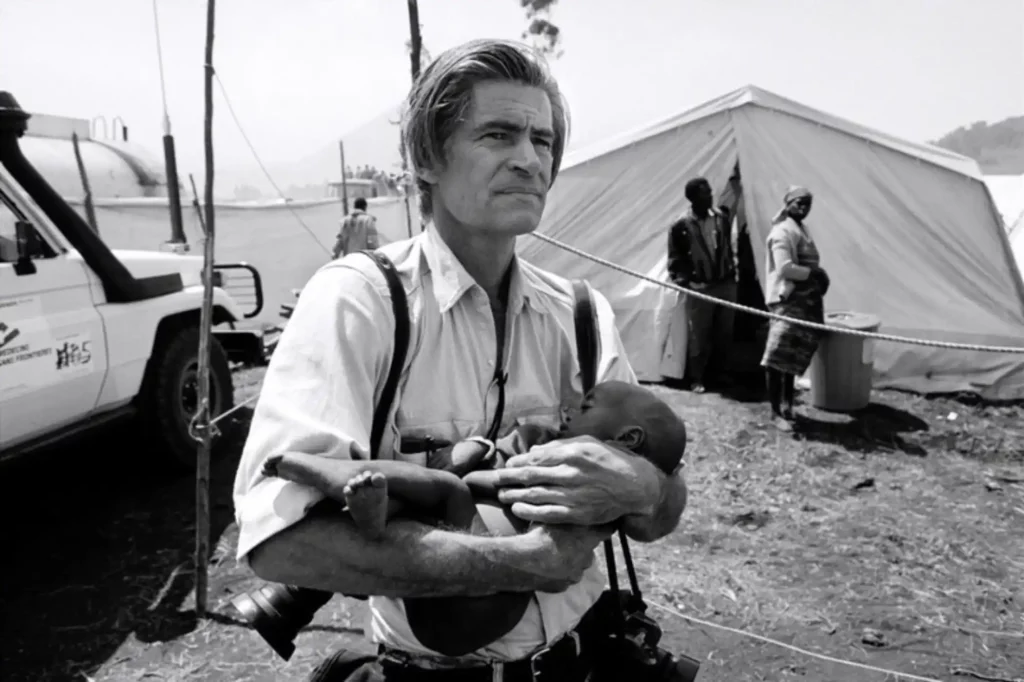

In the same vein, we can also mention James Nachtwey, an American photojournalist who covered war zones and humanitarian crises for nearly forty years. Through his powerful images, he draws attention to the effects of extreme poverty, hunger, and social injustice.

His striking and often violent photographs leave a lasting impression. Hell follows one tragedy after another: orphanages in Romania, drug addiction in Pakistan, cholera in Zaire. This award-winning photographer has documented some of the world’s most harrowing events, capturing the fury and hell through impeccable framing. His uncompromising portrayal of the world is sometimes a reality that needs to be seen.

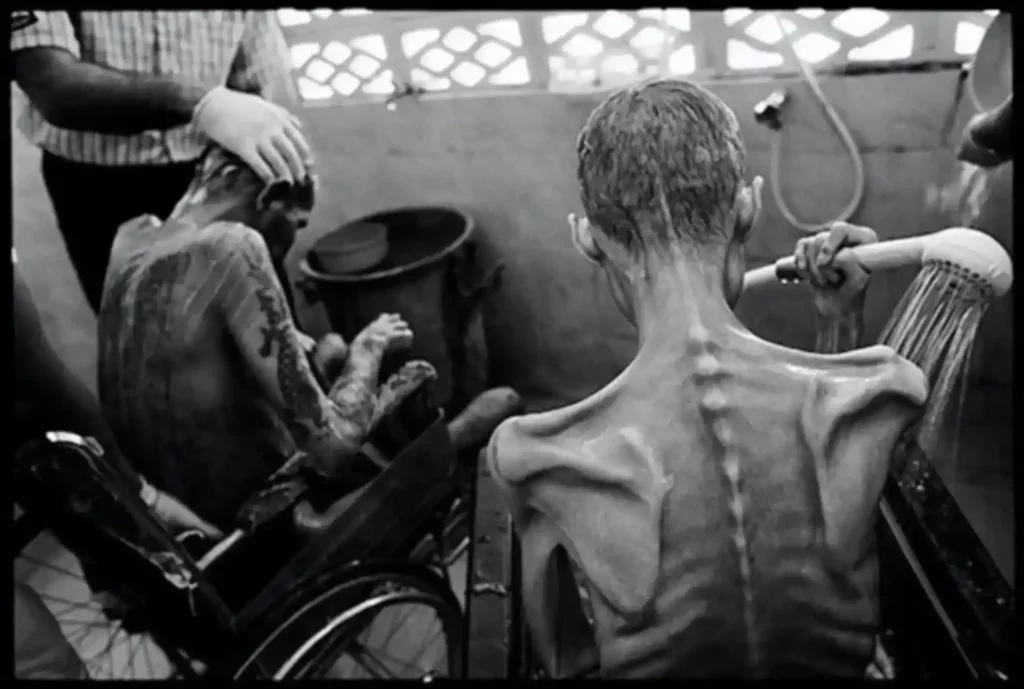

It is impossible not to mention the work of Eugène Richards, whom the newspaper Libération referred to in an article as “the Nobel Prize of the wound.” Here, too, the battered lives take center stage. Addicts, psychiatric patients, and homeless people are the subjects of Richards’ photography. He steps quietly into their worlds, capturing intimate, desolate, and heartbreaking everyday realities. This closeness, which Richards cultivates with great discretion, even invisibility, forms the hallmark of his visual signature.

“This is what the people I have photographed often tell me afterward. It sometimes makes me question my own personality, so easily forgotten,” explains Eugène Richards, who is little known to the general public. His close-up framing, focusing closely on faces, and his off-center compositions that direct the gaze toward often insignificant details reflect the tiny, unstable lives he captures. These chaotic lives disturb our eyes, which have remained in their comfort zone.

Photography Involved in Community Engagement

While the new generation of photographers is just as committed as the previous one, they are increasingly involved in supporting communities. It’s no longer just about being witnesses to these unbalanced lives, but about intervening in their lives, even raising funds through their photographic work. The idea is to offer a different perspective, another way of seeing life, in order to help people bounce back and seize every small opportunity.

Stéphanie Sinclair is an American photojournalist who fights against child marriage worldwide. Through her images, she denounces this ancient practice. To amplify her testimony, in 2012, she created an NGO called “Too Young to Wed,” which allows her voice to be stronger and more invested. While continuing her work, she also encourages young girls to fight back by offering them cameras to document their daily lives. The United Nations, recognizing her dynamic efforts, supports her engagement by building awareness campaigns for the countries involved.

In 2016, Cyrille Bernon, a photographer sensitive to humanitarian causes, volunteered at the Idoméni camp in northern Greece, where he met exhausted families who were relieved to finally be on European soil. However, disillusionment came quickly as Europe decided to shut down the camp later that year. Faced with this vulnerable population, Bernon took his cameras to document the despair of the 5,000 children among the 15,000 refugees living in inhumane conditions. His photo essay “Une enfance dans les camps” (A Childhood in the Camps) was awarded twice.

His commitment continues as he brings this testimony to schools to speak of the unspeakable and to ensure that the privileged European child generation remembers.

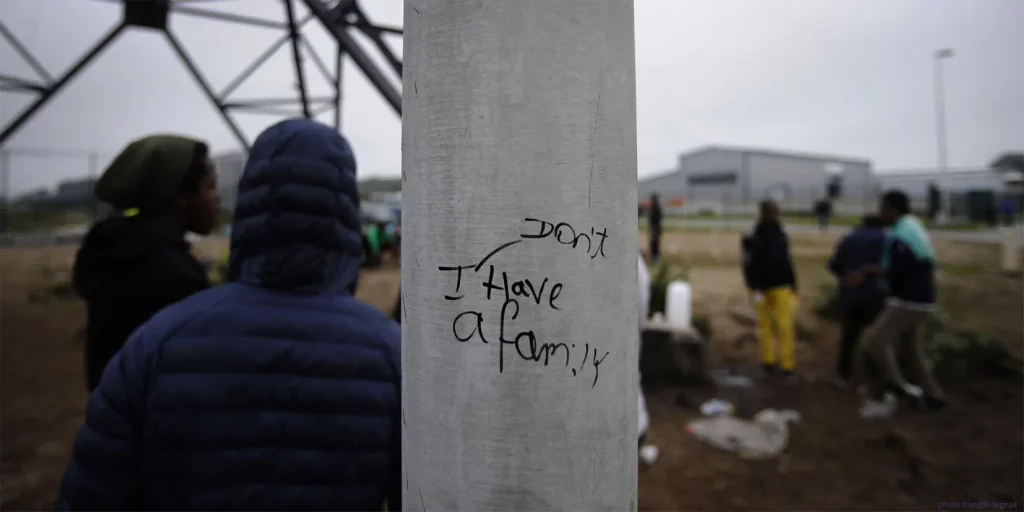

We also mention François Legeait, another photographer deeply engaged with populations forced to flee their homeland.

Ruddy Roye, another committed photographer living in Brooklyn, documents the world around him. Through his portraits of African Americans, always accompanied by poetic texts, he strives to break stereotypes and offers a profound reflection on the individuals that society has chosen to ignore.

His work provides a powerful look at the human condition, whether in New York, Jamaica, or Cleveland.

As we can see, the list of photographers who take a stand and fight for causes is very long, and it’s impossible to mention them all: Frédéric Noy, who focused on the LGBT community in East Africa; Dominika Cuda, a former high-level athlete who supports young athletes lacking resources. She publishes an annual calendar of photos, highlighting the beauty of athletic bodies, with the profits being donated to charitable causes.

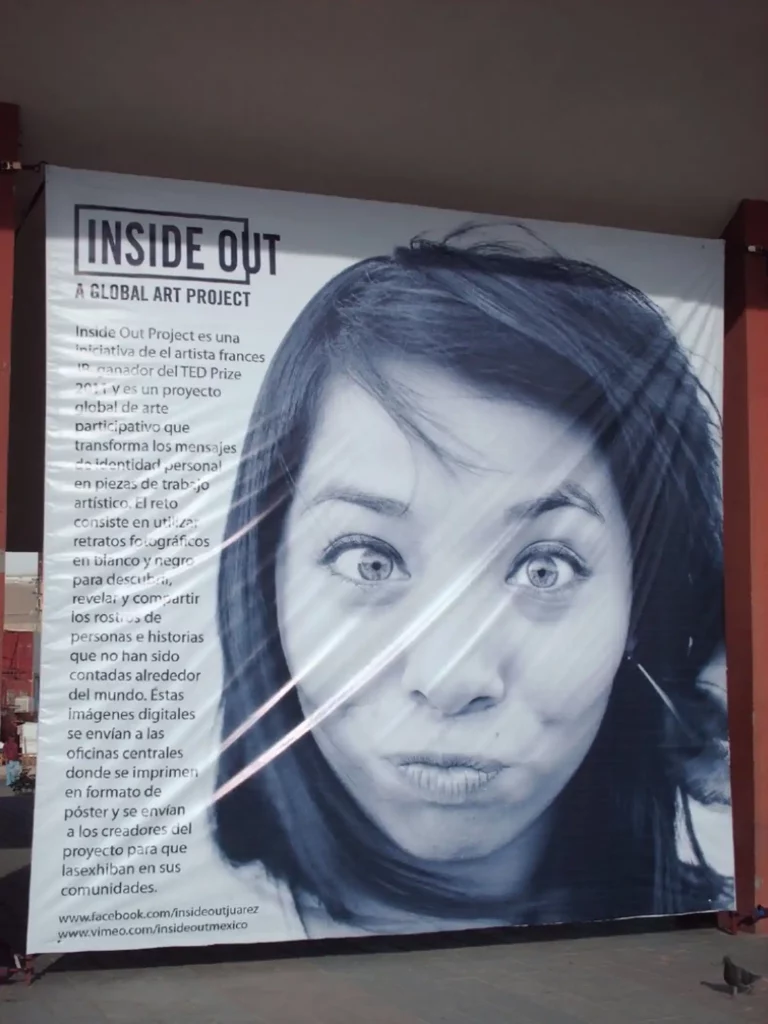

JR, internationally renowned for his participatory art project Inside Out, which invites people to display their portraits in public spaces to support a cause, such as in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, where the faces of victims of violence or crime were posted.

To close this beautiful list of photographers engaged with the most disadvantaged, a special mention goes to Dmitri Markov, the Russian social photographer who passed away in February 2024. He created an exceptional portrait of his fellow citizens, far removed from the elites and the gilded world of Moscow. A trained educator and a volunteer at an orphanage, this self-taught photographer, armed with only his iPhone, was able to capture the very essence of his compatriots—those who are marginalized, adolescents without hope, where alcohol and drugs are part of daily life.

His graceful movement, soft and perfectly controlled color palettes, make these scenes of life all the more powerful and poignant. This unique perspective will be deeply missed.

Conclusion

Poverty is such a pressing issue in today’s world that it is not surprising that so many photographers turn their gaze towards the lives affected by this scourge. Political crises, climate change, domestic violence, wars, famines, epidemics, illness, unemployment—these are all factors that can push individuals or families into poverty.

Competitions like the National Geographic’s #EndPoverty campaign or awards such as the Caritas Photo Sociale have helped shed light on these essential testimonies about this reality, which is often underrepresented in the media in general.

In 2024, the association L’Œil Sensible is expanding this prize to include more actors and partners, now titled the Prix Photo Sociale. A call for applications has been launched for the 5th edition in 2025. Grab your cameras!