To understand complex subjects, it is not enough to reason and analyze. The emotions provoked by the beauty of an image are a powerful tool for understanding them too. This is what our photographer Carolyn Cheng succeeds admirably in doing. Through her aerial and abstract views of landscapes, she captures the forces of nature at work. Using the landscape as a medium, rather than as a subject, she produces lyrical forms in vibrant colors. She addresses our unconscious and shows nature without dominating it, in a fascinating approach.

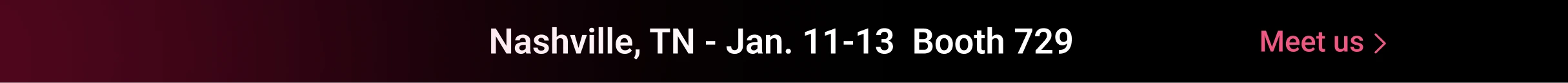

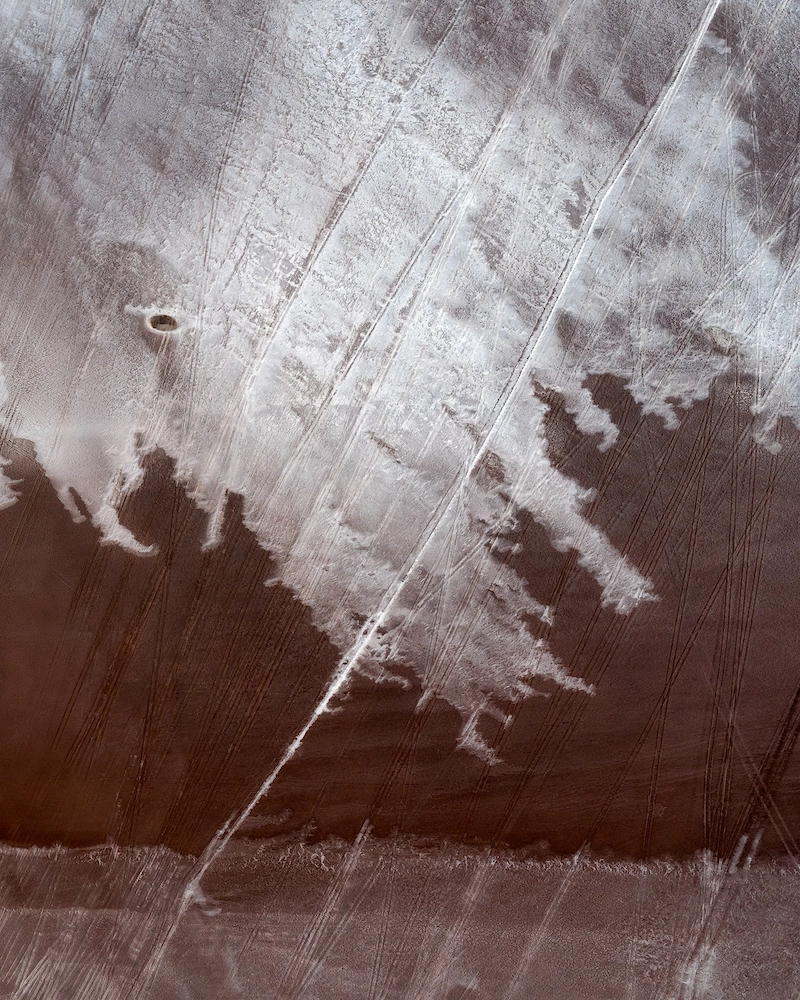

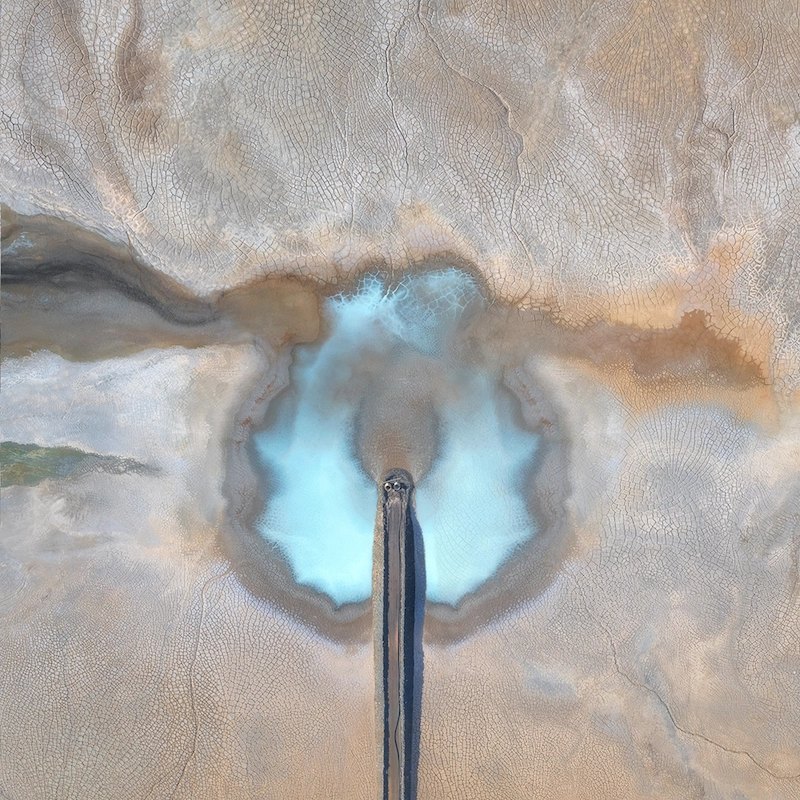

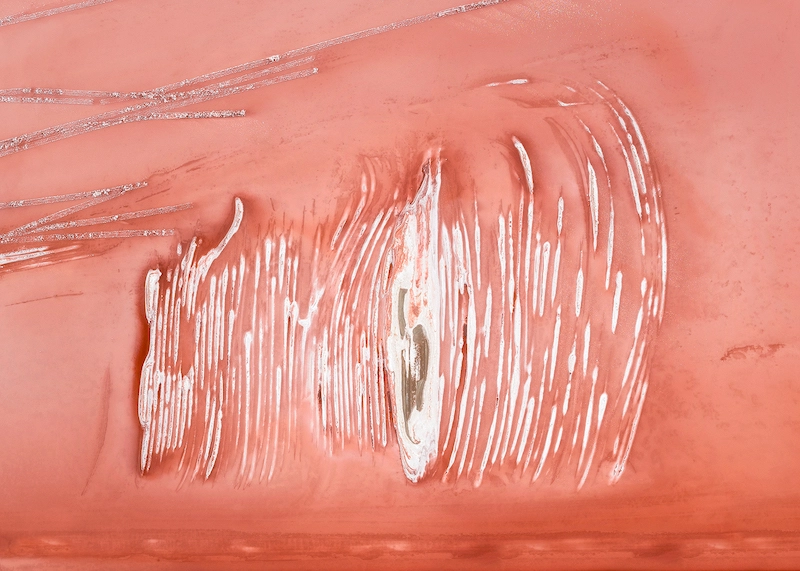

In a recent series of aerial photographs, “Sublime Waste,” her abstract views of mines reveal shimmering colors and strange patterns. This beauty is all the more disturbing because it highlights our harmful impact on the environment. An ambivalence rich in lessons that made us, at CYME, want to know more about this multi-awarded photographer.*

Can you tell us more about yourself? Tell us about your photographic world?

I’ve always been somewhat of a seeker, looking for new challenges and deeper meaning in the world around me. While I have a rewarding professional career as the Chief Operating Officer of Canada’s largest national real estate company, I have also always enjoyed having an outlet for creative self-expression. About seven years ago, when the door on my competitive athletic pursuits closed, photography became that central outlet.

Although I initially pursued photography casually, the moment it transformed from a hobby to a passion was when I discovered aerial photography. Seeing the world from above, where ordinary terrestrial elements like water, sand, salt and earth, combined to form ethereal and otherworldly patterns had a transformative effect on how I saw and experienced the world.

I had such a strong emotional response to this experience that I felt compelled to capture the feelings these landscapes evoked in me, whether they were of natural or altered landscapes.

Of course, through the pandemic, the nature of my photography has needed to evolve without travel, but it’s given me the opportunity to find inspiration closer to home in my local gardens, conservatories and in the studio, making botanical still life work.

2020 and 2021 were seminal years in my photographic journey. My work has been consistently recognized and awarded by PX3 (Prix de la Photographie Paris), IPA (International Photography Awards) and ILPOTY (International Landscape Photographer of the Year Awards). In addition, in the fine art community, I was selected to participate in various group exhibitions. I have also been asked to speak and write about my own work in podcasts, webinars and publications and I’ve been delighted to give back to the community that has given so much to me.

As I return to the air, the pandemic and world events have influenced the direction of my work. The pandemic has required that we photograph more locally, but it has also highlighted that local decisions impact the rest of the world. As I grow as a photographer, I would like to explore some of the local issues where I live that have a global impact. For instance, closer to home, I would be interested in photographing the impact of the Canadian tar sands on the environment.

What made you decide to go deeper into the practice of photography and what do you want to share through your art?

I’ve always been an active person and from my young adulthood into my thirties, I threw all of my spare energy and passion into competitive sports, where I trained to compete in cycling road races on a national level.

Unfortunately for me, racing came at a price. After a number of crashes and through chronic wear and tear, one day I discovered that I could no longer sit comfortably on my bike. So, while the racing door closed, the photography one opened.

The starting point for my photography coincided with my passion for international travel. In the early days, I would take my camera with me on vacation, where I would try to capture the stories of the people and landscapes of the country. As I began to focus more intently on photography, the purpose of my trips became entirely photography-based, where I would produce a body of work from my experiences.

“More recently, photography has become an even more meaningful part of my everyday life.”

More recently, photography has become an even more meaningful part of my everyday life. The time I’ve spent in nature, or with natural subjects in the studio, has brought a meditative and centering aspect to my life which has been enormously beneficial during the pandemic. In addition, as my photography is fairly intuitive and experimental, I find that the underlying meaning behind some of the images reveal themselves only as I delve more deeply into understanding and interpreting the work. In this sense, photography provides me with a means for self-discovery and introspection.

While I do photography for myself, one of the greatest joys I have is when my work emotionally connects with a viewer, whether it’s in a way I intended or not. Sometimes viewers have even shared that the imagery has helped them work through a challenging experience in ways that I couldn’t have expected.

“In these more isolating times, the power to connect with others through visual images and the written word, has been extremely rewarding and meaningful for me.”

You are famous for your abstract aerial perspective. Why did you decide to take up landscape photography?

As I look back on my childhood, I realise that my love of the outdoors was instilled in me by my parents. My childhood home backed onto forested lands where we played and explored on a regular basis. My parents also prioritised spending time outdoors, whether on vacations exploring famous Canadian landscapes or finding interesting hikes at local provincial parks.

As a young adult, my travels would also take me to distant lands, always in search of unique landscapes and cultures. Once I could no longer race, I immersed myself into travel and photography, in the hopes of making images more skillfully and artistically.

In my early landscape photography workshops, I was lucky enough to try aerial photography and became drawn to it immediately. I was attracted to both the exhilaration of the experience as well as seeing the world from a new perspective. In my daily life and work, my mind likes to discern patterns from complex sets of information.

“My mind likes to discern patterns from complex sets of information.”

Being up in the air, I “see” in the same manner as landforms become abstracted into shapes and patterns, which is only possible when seeing the land from the sky.

Interestingly, part of this pattern recognition works on both a conscious and subconscious level. In the air, while I still actively compose my images, I must work more quickly, using intuition that draws from my life experiences and references. I think there is a magic to the subconscious mind and I’m always curious, on review, to see what I have responded to in the air.

Do you like Carolyn's interview?

You love abstract images. What can you express thanks to abstraction and what can you reveal?

As an artist, I am very drawn to the surrealist notion of exploring the realm between reality and the unconscious. While there may be various ways of expressing this dream-like realm, abstraction feels fitting, whether it’s through aerial imagery or through my more recent experimentations in black and white photography with inversions and solarization.

For context, inversions reverse our notions of light and dark and solarization often transforms an image to create haloed contours around objects and an ethereal silvery glow within them to transport us away from our everyday reality.

Specifically, abstract images have the power to communicate emotions. When I am taking my aerial images, I only take them when I have a strong emotional resonance with the landscape. Often something in the geology reflects back a pattern, symbol or metaphor that has meaning to me.

As I have progressed in my journey as a photographer, I find the images that have the most impact on me are those that provoke an emotional reaction. I hope my work also helps elicit an emotional response in viewers.

“Abstract images provide an entry into the world of concepts and emotions beyond their physical reality.”

Through your photos, you claim to “ investigate aspects of the feminine sublime in the natural world.” Could you explain this feminine sublime you are looking for?

The traditional definition of the Sublime started with Edmund Burke in the 18th century and evolved throughout history in European and American schools. In essence, it proposes that the vast scale of nature inspires awe and terror, and taken together, evokes divinity, the unrepresentable and/or transcendence. In some representations, it alludes to humanity’s need to dominate or conquer their terror. While some of these elements are contained within my work, my work doesn’t fully align with this concept.

The Feminine Sublime, on the other hand, focuses more exclusively on the dimension of the unrepresentable or the otherworldly. It doesn’t seek to master, appropriate or dominate the other, rather it idealises a coexistence with nature. When combined with the notion of ecofeminism, it’s a departure from a utilitarian view of nature entirely based on consumption.

My imagery, when you essentialize it, shows symbiotic parts of nature where we see the interplay of water, sand, salt and sediment in a very dynamic form, where patterns are formed, dispersed and then regenerated.

It illustrates the basic cycles of the landscape in its natural state. As the images are taken from an aerial perspective, viewers can’t always immediately comprehend or contextualise the work so it can feel otherworldly.

It’s always such a surprise and delight to me when viewers realise that what is photographed is simply water, sand, salt or earth. In that sense, my work is about transforming ordinary elements into beautiful, moving images that give us a sense or a possibility of the otherworldly. It shifts our sense of perception, in a way, of what exists and what is possible.

“It focuses on the symbiosis between humanity and nature that requires the development of a sustainable relationship. “

How do you find your inspiration?

Inspiration, of course, is all around us, although for my photography, I think it’s fair to say that I draw a significant amount of my inspiration from nature.

During the pandemic, I’ve tried to remain active and connected by going on a daily walk. Over time, it’s become clear to me that walks in forests or by the lake have an immediate calming effect compared to walks in city streets. Being in nature not only calms, but also reminds us that there is something far greater that surrounds us. I love that sense of awe and reverence and seek to share my experiences with others.

Specifically, I like to seek out landscapes that are very different to those I am typically immersed in. As an aerial photographer, I am also drawn to places where the core elements of water, sand, salt and earth are dynamic. In such environments, we not only see the natural cycles within the environment but we also see how changing patterns can create fleeting gestures often capable of evoking emotional responses.

More recently, I have begun to be interested in photographing the altered landscape, as the aerial perspective has a unique ability to tell the story of our impact on the natural world.

After working on several nature photography series you produced the Sublime Waste series. You aesthetically sublimate the terrible “trace” made by man. The beauty of these pictures transports us and creates a tension between intellect and emotion.

What are you trying to provoke with these photos?

My interest in photographing altered lands evolved over time. Initially, I was hesitant to engage in this type of photography as I felt it was important to have in-depth information to contextualize the various environmental issues in a balanced manner, should I publish images on the topic. I knew it would be difficult to do this without access to insiders in the mining industry and amongst environmental activists.

As luck would have it though, on the day I took the images for Sublime Waste, we were in an area with difficult lighting conditions to photograph a very delicate natural area. Our only alternative option for photography was the altered landscape. I decided to adapt and give it a try. I didn’t publish these images until I could wrestle through my concerns.

Does this interview inspire you?

My breakthrough came when I saw an exhibit submission called Seeking the Periphery. The exhibit was looking for images that aren’t typically seen, but rather exist at the margins of our society. This theme highlighted that through city living, we are often removed and disassociated from the means of production, and thus, we can unintentionally ignore the environmental consequences of feeding our consumption.

By highlighting this aspect of the human condition, it could invite conversations to generate awareness about our environmental footprint as opposed to requiring answers to the perfect balance between mining, the economy and the environment.

When I first published this series, I received this comment from a university friend who was a gold mining engineer, “Carolyn, amazing photo of the tailings dam. It works for me on multiple levels, and probably on some that you didn’t necessarily intend but resonate with me due to my time building tailings dams in the gold mining industry. Never has a photo captured my internal conflict of love of nature against my need/compulsion to build infrastructure.”

My friend later wrote to me that after a failed project, he left his job and began working in more mission-based work, only in renewable energy sources.

This image helped him process the emotions he had gone through and this was so incredibly touching to me. I better understood the power of these images after releasing them and it has encouraged me to more proactively pursue this aspect of my photography given the very serious issues our world faces and the tensions that lie across human needs and consumption, limited resources, the environment and climate change.

Could you give us an idea of the equipment you use to photograph these amazing images?

For aerials, I typically have two cameras, although my primary setup is a Nikon D850 with a Sigma Art 85mm f1.4. Around 80%+ of my photographs will be taken with this camera and lens combination. My secondary setup was a Nikon D810 with the Nikon 24-70 f2.8, which I used to capture wider scenes. Recently, I have converted to a mirrorless setup so moving forward, I will be happily using the much lighter Nikon Z7II as my secondary setup in the air!

What kind of editing do you do on your pictures ?

My editing workflow can vary from image to image. For some images, I have an immediate sense of how the image should be processed. Others require more experimentation and I will try multiple approaches before settling on how to bring the image to life. Once I have a clear direction, I proceed to build the canvas. With aerials, for instance, I may transform an image slightly to get it to a bird’s-eye view if it was photographed at a slight angle. I will also rotate the image and try different crops to find the composition that resonates the most.

Afterwards, I will make contrast adjustments, remove colour casts and dodge and burn to give the image the additional visual flow and dimension needed to help move the viewer’s eye through the image. Once the individual image editing is complete, the final step is to curate the images into a body of work. How the work is sequenced has a significant impact on how the viewer experiences the work and can determine whether they engage with it from beginning to end.

Which photographers and/or artists inspire you?

Photographers that inspire me today are Daniel Beltra for his environmental advocacy through aerial imagery, Robert Mapplethorpe and Tom Baril both for their innovations in botanical still life photography and Ori Gerscht for his political and social commentary with botanical still life work.

Beyond photography, I have historically been drawn to post-impressionist and abstract expressionist painters such as Mark Rothko, whose minimalist work has always evoked powerful emotions, Georgia O’Keeffe, whose intense abstract floral paintings deeply resonate and Giorgio Mirandi, whose abstract bottle still lifes inspired me to pursue still life work.

More recently, I have been fascinated by conceptual artists like James Turrell. Rather than using light to create art like most painters and photographers do, his medium is light itself. With light, since there is no object or image to speak of, his art challenges how we see and experience light or, effectively, our perception. The experiences he creates for viewers are typically built in large-scale buildings, museums and more recently, he’s transforming an extinct volcano into a naked eye observatory! The ambition, scale and monumentality of his work leaves an indelible impression and must be experienced to fully comprehend. This is a short introductory video to his work should you be interested.

It’s probably a challenge to combine both activities at such a high level. Could you give readers some tips on how to successfully manage these two activities?

Certainly, there are challenges to managing my career alongside my photographic pursuits. Finding time to do both successfully requires effort and can only be achieved if, in both cases, you love what you are doing.

As I do have a separate career, I have given myself the freedom to pursue my photography in an organic manner, with a focus on continuous learning rather than the pursuit of specific goals with set timelines. With this in mind, here are some tips for similarly situated readers who find themselves trying to manage their careers and photography:

First, I’d say, make sure that photography is something you genuinely love to do. The old adage that doing what you love won’t feel like work applies.

Second, explore your interests in photography and don’t put pressure on yourself. If you feel that you want to do more, then commit more.

Third, find a mentor. As someone with more limited time, a mentor can help accelerate your growth as a photographer more quickly. Take time to find a mentor as this must be a comfortable, natural relationship for it to work well.

Fourth, define a progression for yourself that’s realistic to keep you motivated. For example, in the world of landscape photography, certain landscapes are far easier to photograph and others more complex. By going to landscapes that are easier to photograph before progressing to more complex areas, you will feel a sense of accomplishment and growth that makes you continue to want to learn more.

Fifth, as you progress and develop real competence, start to set realistic and achievable goals focused on the learning and growth process rather than being outcome-oriented. For instance, you can apply to some awards programs, not for the outcome of winning an award, but to measure your progress. Some awards programs provide critique, feedback and/or a scoring system which are all valuable for you to learn. You can also understand your progress over time.

Sixth, build relationships and learn from others. As with any industry, these are incredibly important for learning, camaraderie and for creating opportunities.

Seventh, be curious and continue to try new things. There is always more to learn and you can do more than you think. The journey of a creative is never complete as we are always learning more about ourselves and what we want to express!

*Awards include the International Landscape Photographer of the Year Top 101 Book as well as National Geographic’s Photo of the Week series. She has also received Gold, Silver, Bronze and Honourable Mentions from the PX3 and IPA Awards Programs respectively.