Is there a particular way of representing women, especially in the press? This question is part of the concerns that drive Marie Docher. A photographer and filmmaker, knight of the arts and letters in France, she is committed to the visibility of women artists and artists of color. With her collective, La Part des femmes, she wondered if there was a male gaze in photojournalism, leading to a bias in representation.

During an analysis of two major French media outlets, focused on photography, she found that 85% of the 108 portraits in one were entrusted to men, compared to 93% in the other. Does this essential male perspective include biases? How can one detach from it? How has this analysis influenced Marie Docher’s work, and how does she address the question of representation?

This March 8th, International Women’s Rights Day, is a great opportunity to reflect with this photographer who doesn’t hesitate to stir things up, both through studies and her work.

After Analysis, 94% of Press Photos Are Taken by Men

You analyzed the portrait photos in Libération and Télérama. What led you to conduct this investigation, and what was your intention? What are the major insights you gained from it?

During the second lockdown, with my collective La Part des femmes, we analyzed a sample of the French national press and found that 94% of the photos were taken by men. However, photojournalists claim that their perspective is neutral. We wondered if this state of affairs had an impact on our representations. To find out, we chose to analyze two recurring and prestigious photo sections: the back-cover portrait of Libération (daily) and the guest portrait in Télérama (weekly). Our intention was truly to understand whether the predominantly male nature of documentary photography had consequences on representations.

This work allowed us to analyze over 1,000 portraits and to show that there is indeed a real “male gaze.” Laura Mulvey, the British filmmaker, demonstrated that there is a masculine gaze in films, not solely carried by men, but also by women.

“We wanted to know if there was a “male gaze” in documentary photography, in photojournalism, in press portraits. And yes, there is one.”

Did the result surprise you?

No, not really, because there were many aspects that we intuitively understood. Except that here, we actually showed it and even discovered things we hadn’t imagined.

Unstable or Ground-Level Positions Are Reserved for Women, Gays, or Racialized Individuals

You also conduct an aesthetic analysis of these portraits and note similarities in portraits of women. What are these similarities?

We didn’t exactly conduct an aesthetic analysis, but rather an analysis of positions, environments. We noted similarities in certain portraits of women.

For example, when we gathered photos of individuals photographed on the ground or with an extremely dominant viewpoint from the photographer in the same folder, we realized that over 80% of the people photographed were women, regardless of their backgrounds, social classes, or occupations.

And when the individuals photographed are men, then they are gay, or black, or Arab. This indirectly shows that white men do not represent themselves in unstable situations or in positions on the ground. But they don’t hesitate to do so regarding women, gays, and people of color. This happens unconsciously.

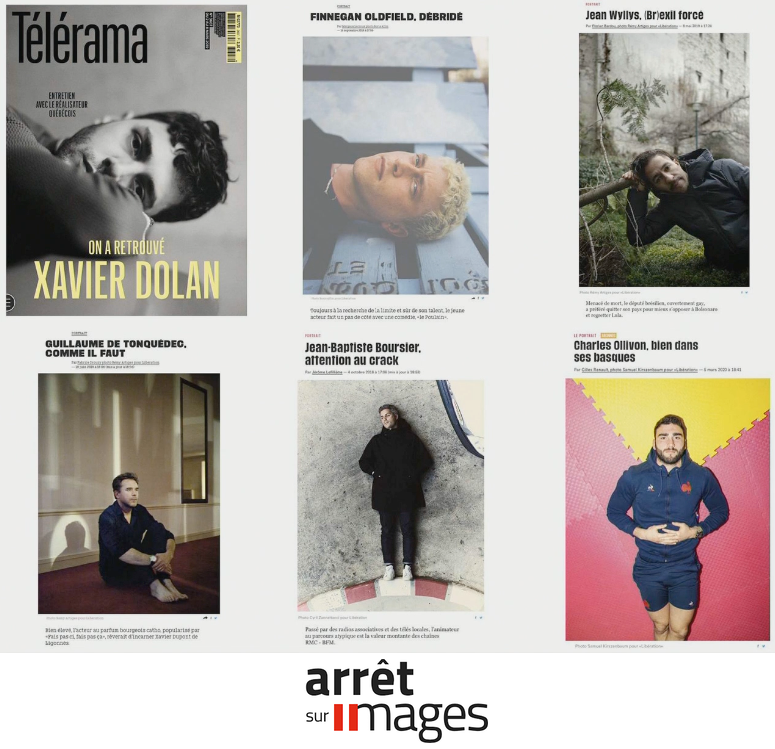

Portraits of Men in the Press

On the contrary, what are the representations commonly found in portraits of men?

Straight men photographed by straight men – and also by women – are all quite homogeneous. They are predominantly depicted standing, firmly planted on their legs. Their skin is rarely visible: they do not wear T-shirts, open shirts, or go shirtless. They are in stable positions, in uniform tones of blues, grays, blacks. This is the biggest stereotype – one that we almost didn’t notice -: white supposedly straight men are portrayed as stable men with nothing to distinguish them.

We find this in weddings where women are expected to be elegant, to have colorful, varied outfits different from their neighbor. While all the men are dressed the same.

Do you like Marie's interview?

After the Study, 60% of Portraits Are Made by Women

Your investigation dates back to 2021. Did your analysis make a difference?

Yes, fortunately. This investigation gained visibility, especially thanks to the editor-in-chief of Arrêt sur Images [a paid digital media], Emmanuelle Walter, who suggested doing a program on the subject. None of the photo editors from the two newspapers wanted to participate. Only the photo manager of Mediapart, Sébastien Calvet, agreed. It was very interesting because he has worked as a photographer, as a photo editor at Télérama and at Libération. The program was so well-received that subscribers asked for the video to be made available for free online. The next day, the photo editors of Libération were calling women, people of color photographers left and right to say that it was an important issue for them. The following month, over 60% of the portraits were taken by women… which just shows that it was simply a matter of deciding to change it.

How Stereotypes Persist

Is it through the training of photographers that these stereotypes are perpetuated?

Yes, and not only that. They are perpetuated through everything: advertising, films… In fact, we live in an environment heavily structured by the male gaze, by a dominant male perspective. Even though voices are emerging and public policies are attempting to change things, particularly in cinema. But this world goes in circles because in photography schools, it’s the former photographers who come back to teach and give talks. It’s also cyclical in photo books, as Ingrid Milhaud writes in an article that will accompany the publication of our study around March 13th.

Becoming Aware of Representation Biases

What changes when it's a woman behind the camera, especially when she's photographing other women?

Often not much because women are in the same boat, with the same references. The important thing is to change perspective and be aware of what’s at play, of the relationship one has with the people being photographed, of how one photographs them.

There are women who photograph like men and men who photograph differently. Beyond biological sexes, these are mental representations. Bettina Rheims photographs like a man, as do lesser-known individuals. With this program, women realized that they reproduce stereotypes.

The interest lies in taking a different look at our practices. Since men structurally hold more dominant positions, there are aspects they don’t see, and women should be able to show them differently. The same goes for Black individuals. I see it with the book I made about lesbians. I don’t believe a heterosexual woman or man could have done this work because there are also questions of trust and knowledge that are important and complex.

Does this interview inspire you?

Co-Constructing Portraits

How has this analysis influenced your work as a photographer?

It has had a major influence. I understood why, for a long time, I didn’t do portraits. I did other things because I was afraid of misrepresentation. I belong to a social, sexual group – I am a lesbian – and, like all those of my generation, I sorely lacked representations. When they existed, they were problematic, made by men and for a masculine gaze. So I didn’t do portraits. The two photo editors of the magazine La Déferlante knew I was working on this study that unravels our way of doing things, and they offered me to do portraits. I was very stressed, but I understood something with this study. I don’t work in the same way anymore.

I work by taking people into account, by co-constructing the images. For example, for my book “And Love Too,” each person was photographed where they wanted, how they wanted. There was never a dominant gaze, no control. It was a collaboration.

The Political Influence of Photos

Your latest book, which blends photos and interviews, was sparked by the debates in France in 2012 surrounding Marriage for All. How is your photographic work political?

My latest book originated from a commission on documentary photography, commissioned by the French National Library (BNF) by the government, where I was a laureate. Otherwise, I would never have done this project. I wanted to ask questions because despite the saying that a picture is worth a thousand words: it’s false.

For minorities, it’s not. Ten years ago, during the debates about marriage for all, we heard a lot from gays, and opposed women and men, but not lesbians. It was important for me to ask them questions and to ask how their lives had changed in the last 10 years after the events of 2012, which had been very violent. To know how we were doing.

This work also involves taking a different look at portraiture, at photography, and that’s very important. I talk with them about the intimate and the intimate is political. In 2012, we saw that what concerned our bodies, our families, was thrown into the public square.

Everyone had an opinion on it, and they didn’t ask for ours. It was time for lesbians to have positive and real representations.

“Making the invisible visible and showing realities that are marginalized, that’s political.”

Representing Lesbians

The book includes several types of portraits: nudes, very posed portraits, or ones taken in action. How did you construct your images?

Each person chose to be dressed, nude, nude on a motorcycle, in nature… The portraits aren’t very posed. The shoots were quite lively. They were fairly joyful exchanges. The images were co-constructed, which means there’s a lot of diversity. There’s no template. It shows our diversity.

I have in mind the work of Zanele Muholi: she directs the shoot a lot, asks to place the gaze in a certain place. I didn’t work like that at all.

“We are inhabited by stereotypes and we need to question them.”

Did you consider questions of female representation in photography from the beginning of your photographic work?

No, I didn’t specifically consider the question of the place of women. The question of the representation of lesbians, yes, I did consider.

Representing the Body and Its Aging

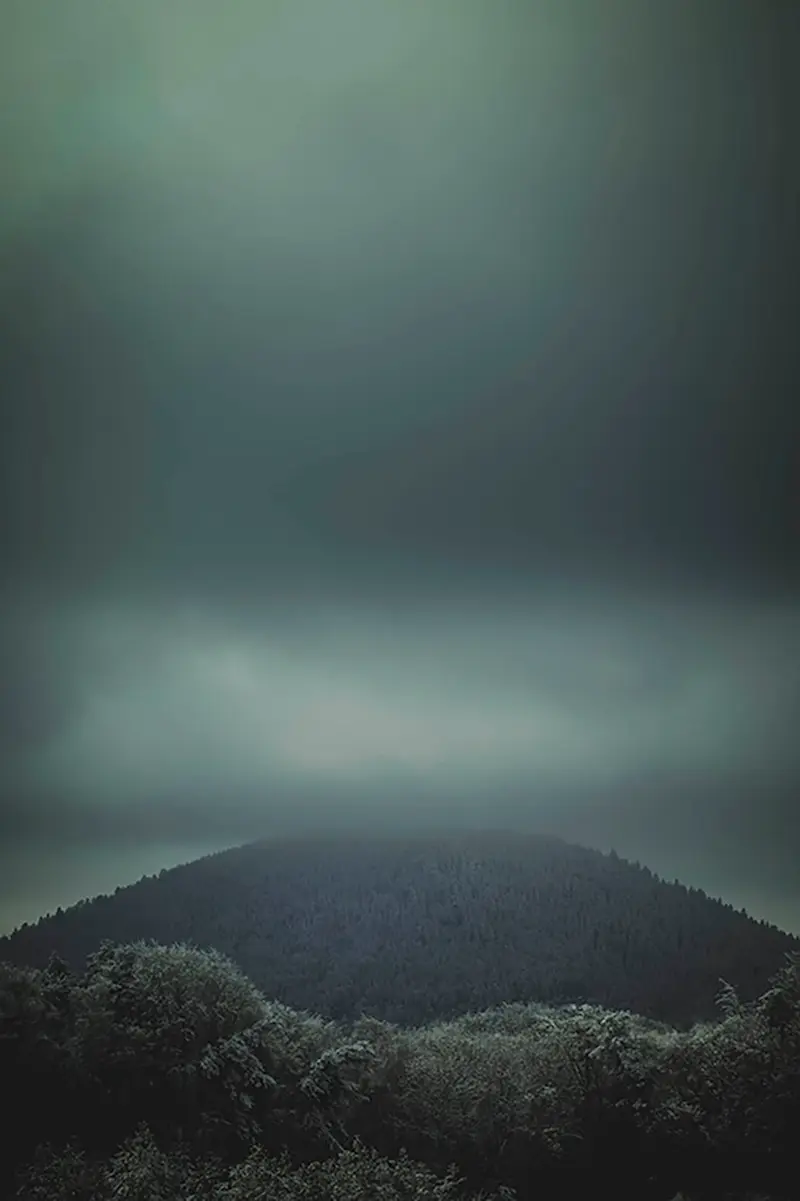

In another of your photographic series, "S'enforester," you merge the body and the forest. How did this return to the land influence your vision of the body?

I have always been deeply rooted in the land; fortunate to be born in Auvergne and raised amidst both urban bustle and rural tranquility. Spending my vacations and Wednesdays on the edge of the forest in the mountains nurtured a profound connection with nature, one that I carry within me to this day. This volcanic region holds a special place in my heart, shaping my identity. Questions about the body appeared later.

I have worked extensively on self-portraiture, an exploration often found among women seeking a more faithful representation of themselves.

I was very involved in activism since 2014. It was a lot of work, and my artistic and professional work suffered from it. One doesn’t become feminist without consequences. Three years ago, I recognized the need to rekindle my passion for art, my true calling.

Initially guided by a poetic sensibility, my practice evolved as I delved into feminist theories, particularly those of Camille Froidevaux-Metterie, whose insights into the female body resonated deeply with me. Now, at 61 years old, as my body ages, questions of representation loom large.

During an artist residency in Finland, I seized the opportunity to explore these themes further, embarking on a journey of self-exploration through photography. My aim was to capture the essence of aging, set against the backdrop of the natural world that has always been my sanctuary – the forest.

“S’enforester embodies this quest to maintain a profound connection with nature.”

Equipment

What type of equipment do you use most often for your shots?

I primarily use a Canon 5D Mark IV paired with a 50mm lens, and occasionally a 100mm macro for portrait shots. Additionally, I have a LED tube for lighting, although I seldom rely on it. This tool assists in adding a subtle fill light to indoor photos. Notably, I avoid using a tripod, as I believe it’s crucial for portrait work to maintain a sense of agility and approachability. This enables me to move swiftly and remain lightweight, fostering a relaxed atmosphere during shoots.

Post-processing

Do you do a lot of post-processing on your photos?

It depends. For a series like “S’enforester,” there is a lot of work because I mix images, but otherwise for the portrait series, not at all, except for color balancing. The files could be printed directly.

Advice for Young Photographers

What advice would you give to a young photographer who wants to become a professional?

To be aware that it’s not a lucrative profession. I would tell them to listen to the “Arrêt sur Image” program, which had a lot of impact, to question their perspective. To read the book we’re going to make on portrait photography, which will obviously leave a mark. We show things that have never been shown before. The goal is not to say what to do but to ask questions.

It’s very important to join a union, to learn about your rights, duties, how to make an invoice, how to position yourself with a gallery, buyers because it’s not taught enough and it often puts people in embarrassment.