Today, we are immersed in a civilization where images are omnipresent.

It seems normal to us to see images appear, to create them ourselves with a single click, but do you have any idea of how photography was born?

How photos actually came to be? Who were the creators of this exalted invention? Do you have any ideas?

Let’s retrace in a few broad lines this fabulous (and a bit crazy) epic of the image.

Darkroom's mystery

First of all, we should note that it requires the sum of two parts, optics and chemistry, for the photo to exist: a darkroom, a camera obscura, and a developer.

Try it out in real life: imagine yourself in a room completely closed, where you only let the light in from the window through a tiny hole. You are in the dark.

A few moments later, you can see an image (of your street) appear on the wall in reverse. Explanation: the light rays that penetrate an optic (in this case, the small hole in your window) send the image backwards.

Our brains are used to turning what our eyes see right side up, which is more practical. But let’s continue the experiment: if you put a specific chemical medium, such as silver chloride, on the wall of your room, then the projected image will print itself; it will fix itself on this medium and become a photograph. Simple, isn’t it?

Historical dive with Niepce, Daguerre, Fox and Lumière

Although, the first camera obscura is said to have been created in 1671, a more elaborate light machine was devised by Nicephore Niepce in 1816 to capture images. A few pioneers in turn added to the photographic tower and made the technique more sophisticated. However, these images had a flaw: they gradually faded in daylight.

Building on their work, Louis-Jacques Daguerre developed the principle that would become the basis of the camera.

In 1838, Daguerre developed the principle that would take his name: a direct positive on a copper plate coated with pure silver and exposed to light. The daguerreotype was born. It was a photograph, but it could not be reproduced. Another invention quickly followed the first: immersion in water saturated with salt finally made it possible to fix the image definitively. In 1839, we can say that photographic development was born.

Five years later, William Henry Fox developed the calotype, an intermediate negative that would finally allow the same image to be multiplied. The photo thus became reproducible! This negative-positive principle would be used until the arrival of the digital image.

The arrival of the shutter in 1880 further improved the exposure time and, therefore, the quality and intensity of photography. As for colour, after a few early attempts around the three primary colours–red, yellow and blue–it was the brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière who, in 1906, proposed the autochrome.

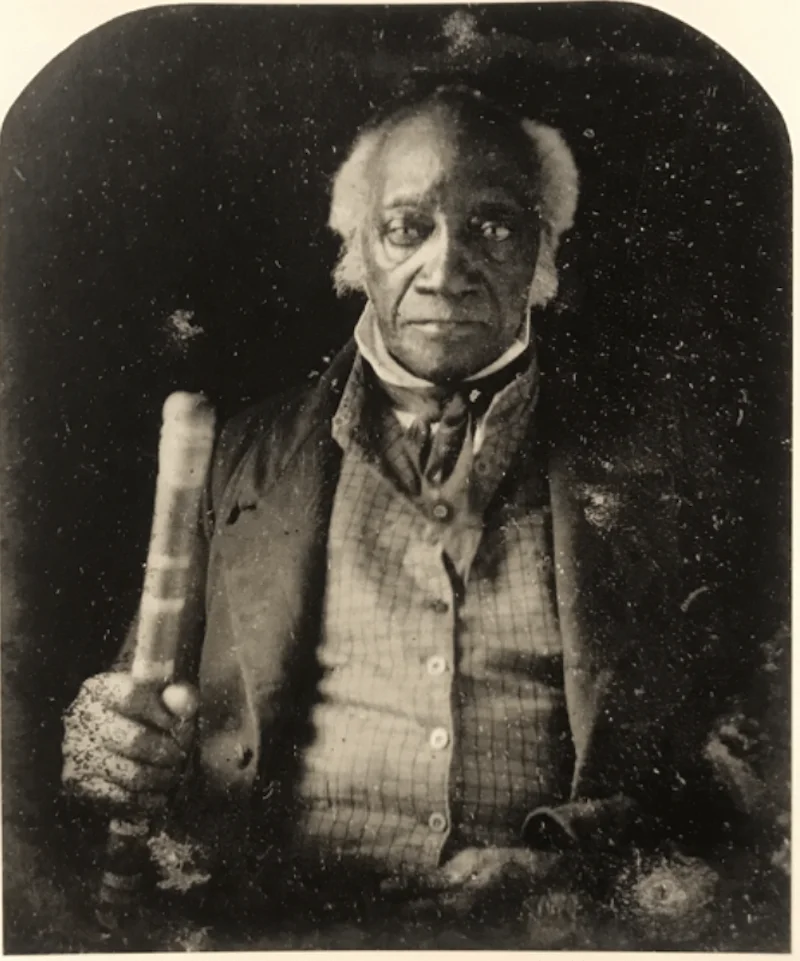

With the advent of all these wonderful inventions, photo studios would soon appear in Paris. It was common to go and have your portrait taken by these photographers who handled the camera with dexterity. Nadar, who immortalised many celebrities such as the great tragedienne Sarah Bernard, and the poets Rimbaud and Baudelaire; Gustave Le Gray, who became the official photographer of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte; Eugène Disdéri, who created the visiting card holder (the ancestor of the photo booth, so to speak); and Emilien Sully, a hatter who became a photographer and distinguished himself at the International Exhibition of Photographic Art in Algiers in 1910. Wealthy industrial families were fond of photographic portraits of couples, children, and individuals. Photography was popular because it was less time-consuming and faster than painting.

In Pioneer's wagon

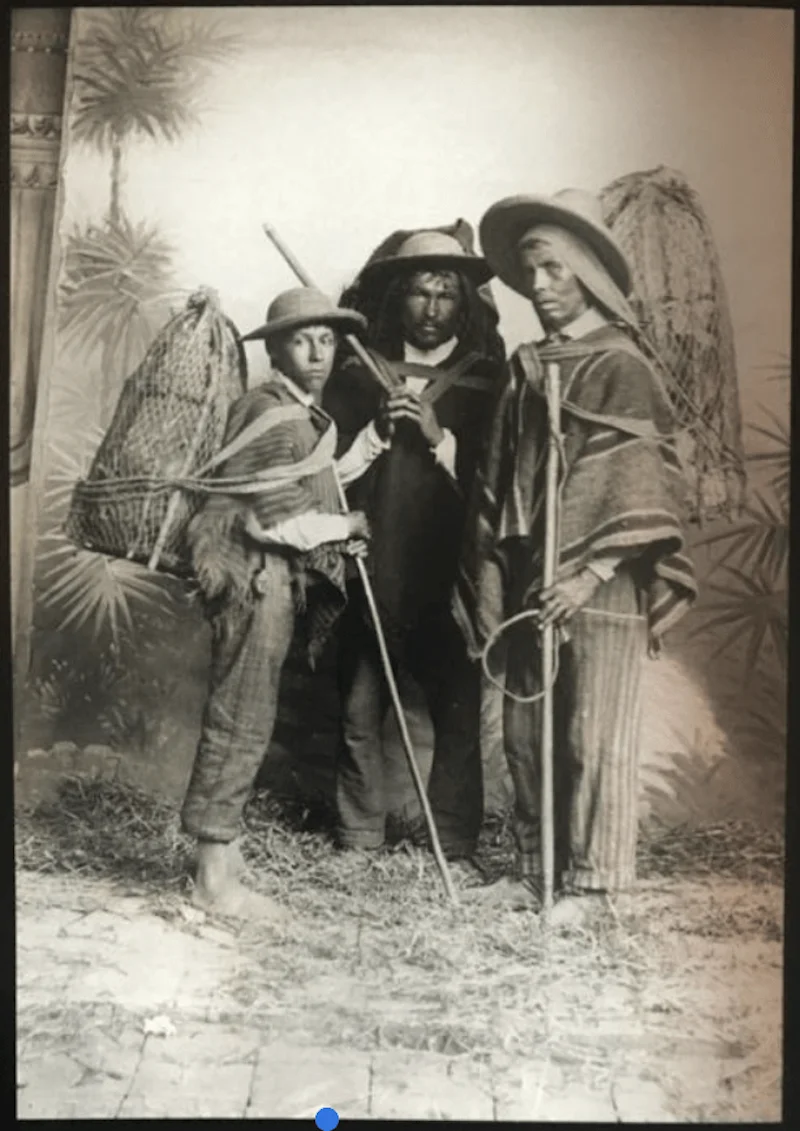

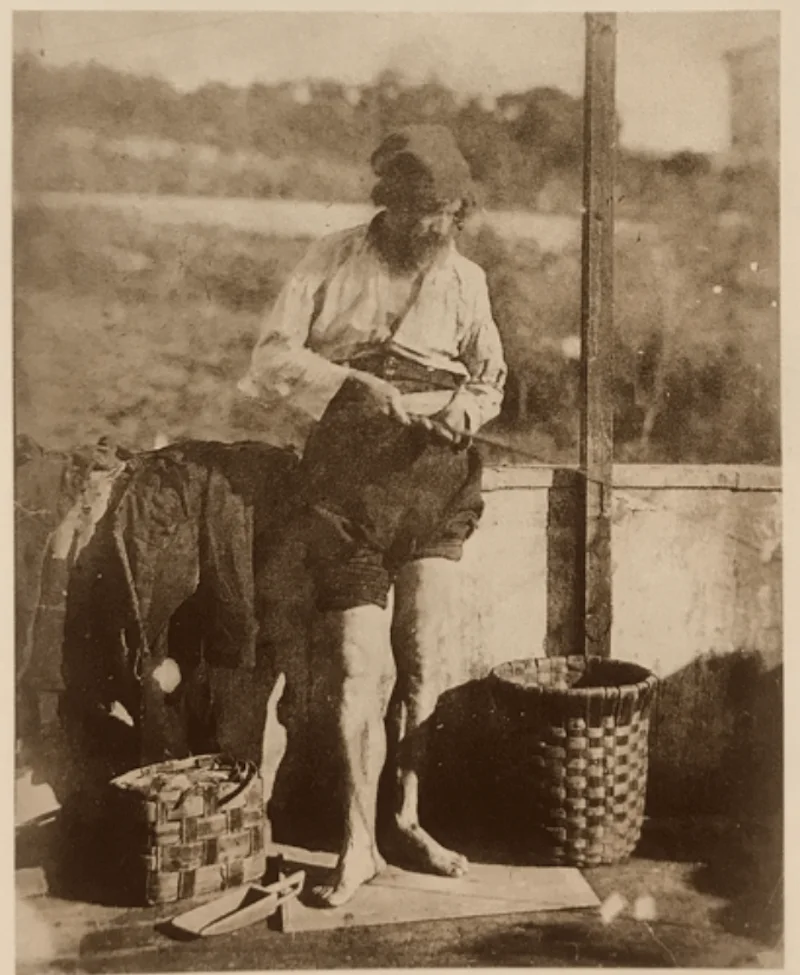

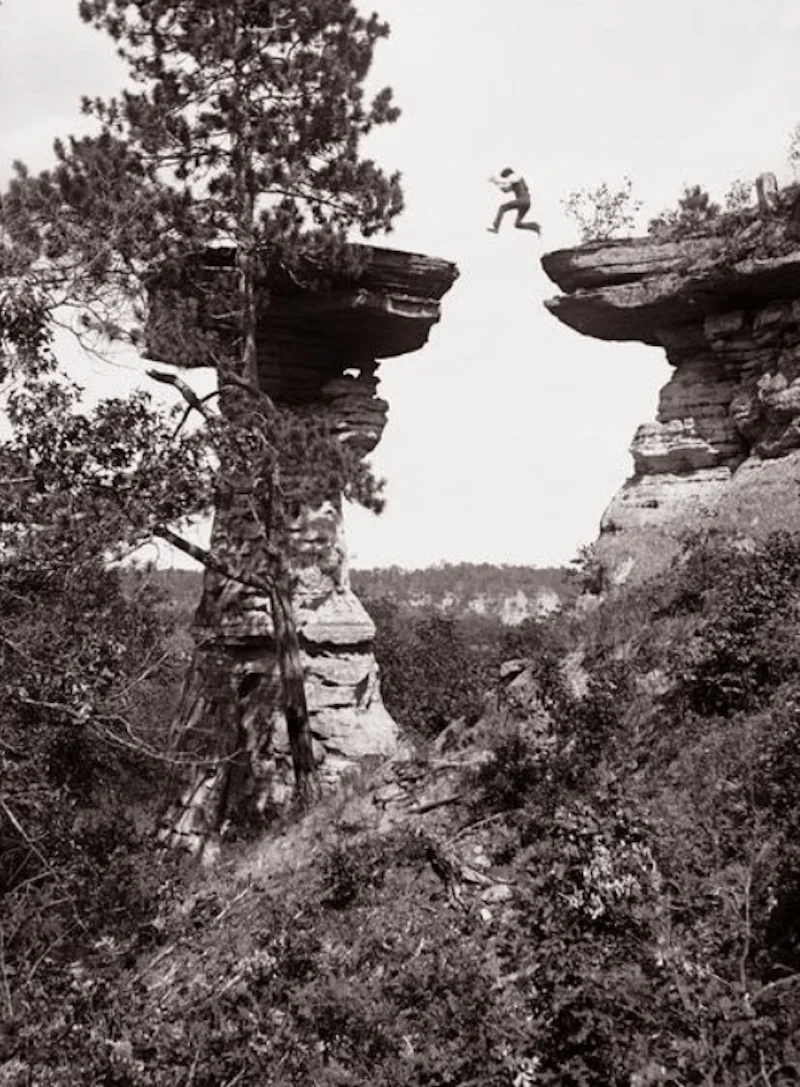

The mid-19th century was characterised by a taste for discovery, particularly nations, peoples, sites and landscapes. Photography became an essential tool for explorers. Despite the technique’s cumbersome nature (camera, tripod and large film shots), some photographers became itinerant and did not hesitate to travel the world. Let us mention two of them.

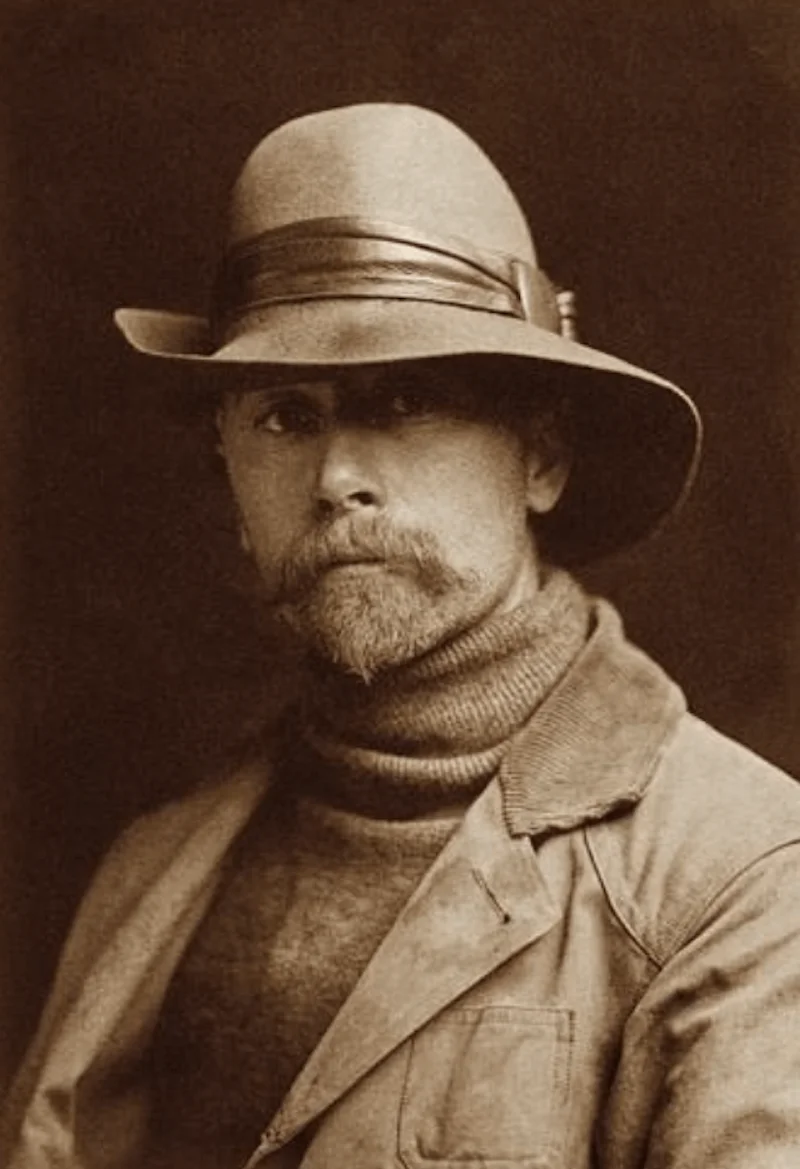

Edward Sheriff Curtis is undoubtedly the most exceptional ethnologist photographer. He dedicated his life to taking pictures of the American Indian tribes with his camera and created the photographic heritage of these native people.

At that time, cameras were constantly evolving. The modernity of photography was underlined by an increasingly short response time, which, of course, modified its relationship to current events or an event taken on the spot. Smaller, more manageable cameras with shutter release allowed fast shooting: “You aim, you shoot.”

The devices of instantaneousness

Ernest Bourgarel,* a French diplomat who travelled the world at the end of the 19th century (Asia, Middle East, Latin America) and French ambassador to Colombia from 1895 to 1900, quickly grasped the interest in photography. He was one of the first buyers of George Eastman’s (Kodak) invention in 1890, the first portable camera with flexible film (cellulose nitrate) that would replace fragile glass plates. The Kodak revolution had just begun.

“The Eastman Kodak brought instantaneousness,” explains Charles-Henri Dubail, editor and custodian of the Bourgarel Fund. Thanks to this small camera, which was certainly not very efficient in terms of image quality, everything became possible: taking a picture of someone walking towards you, of armed men passing by. The camera technique, which required a “mule train” to move and whose rendering was more static and less lively, would soon disappear and, with it, the “Ave de paso” (the bird of passage) as the itinerant photographer was called in Latin America at that time.

The principle of the Kodak system? Eastman sought to simplify operations. It reduced the separation between taking a photograph and the part left to the specialist, i.e., the development of the images: “Press the button, we’ll do the rest” emphasized the advertisements.

*Bourgarel, le Colombien” – French’s trip Diplomat in 19th Century Colombia, (ediSens, 2017).

The tiny vintage shop of instantaneousness

Who remembers “Clic clac, merci, Kodak” ?

The Kodak brand, created 140 years ago, was truly revolutionary because it was aimed at amateurs. The world of photography was becoming simpler.

The memory of every family would be nothing without Kodak. Remember the shared moments of your parents, immortalized by the yellow reels, the arrival of the Instamatic with its film inserted in a cartridge, and then the tiny yellow cardboard cameras created later, which made the happiness of neophytes and children?

What is less known is that the inventor of digital photography in 1975 was Kodak. They had designed a prototype called “filmless photography” that had a definition of 0.01 megapixels! But alas, the giant made the worst strategic choice: it decided not to market its innovation for fear of killing the film market, which was dominant at the time. Sony, Canon and Fuji would soon surpass Kodak. In 2012, it was time to liquidate.

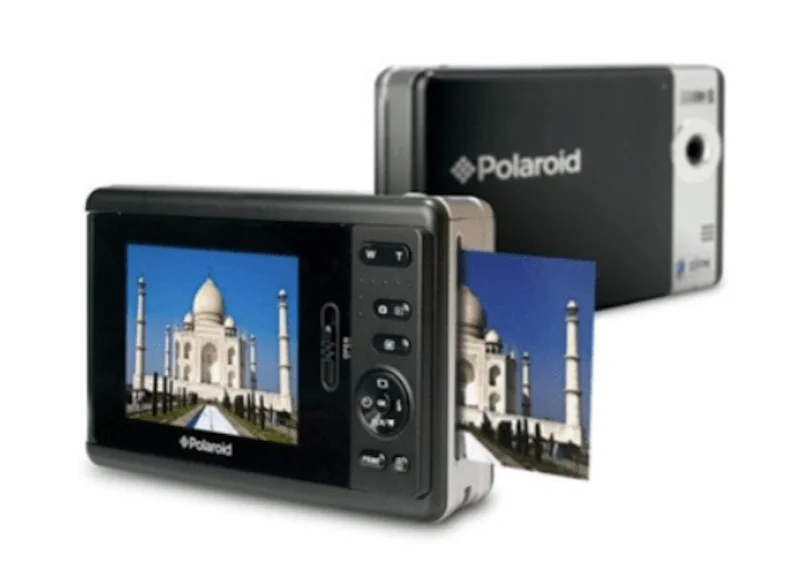

Polaroid, the freshly baked bun

Polaroid was also a product that truly shook up the world of photography.

The Polaroid company developed an instant development process in…1948! Amazing!

This all-in-one camera was very popular with amateurs, who snatched it up despite the relatively expensive cost of the cartridges. It was also very popular with professionals, who used it as a test to control their light during their shooting. As for explorers, they didn’t hesitate to carry a Polaroid in their bag, ideal for offering instant portraits to certain distant ethnic groups. An almost magical object!

In 2009, Polaroid also switched to digital. The Polaroid Two was created, a 5-megapixel digital camera with a built-in printer that allowed you to select the photo you wanted to print. We salute this latest digital version’s frugal and economic dimension, but it did not meet with the success we might have expected.

Argentique? Did you say argentique?

Silver photography owes its name to the light-sensitive film that was exposed to light. This plastic film was covered with an emulsion, a kind of gelatin containing silver and iodine ions. That’s about as far as the chemistry goes!

But in fact, we have only really been talking about film since the year 2000. Do you know why? It was necessary to distinguish between traditional photography, known as silver, and the new, digital photography.

Leica, the big slam

Back in 1905, a German engineer invented the 24 x 36 mm negative. His brilliant idea? Borrowing from cinema, the 35mm film used a horizontal panorama to increase the width of the shot.

In 1924, the Leica company created a compact camera with a fixed lens of exceptional quality (the Leitz lens, still in use today) and its famous 24 x 36 film. A real Rolls Royce!

Leica introduced simple, light, robust models that would seduce (and still do today!) several generations of photographers. The Leica-M was the camera of choice for Henri Cartier Bresson, Robert Capa, Robert Doisneau, Edouard Boubat and Marie-Laure de Decker…. Since 2005, Leica has been in digital mode. The M9 is the ultimate and most elaborate version.

From grain to pixel

The digital age has changed our perception of photography and our relationship to it. We no longer count the number of shots we take, thinking about our limit of 36 views and the price of the contact sheet. We rectify the frame or the luminosity immediately because we can instantly visualise our work. With AI, a blurred photo becomes clear again, and the applications dedicated to photography rectify, straighten, recolor, remove a character or propose a bright blue sky. It’s hard to miss an image, even if we know that more than 80% of a successful photograph is due to the eye and not to the tool. Its easy distribution and archiving are also significant advantages.

On the other hand, film offers better quality in large-scale prints. Digital still struggles with definition when enlarging.

“I look for the pixel to situate the photo in time,” explains Olivier Thomas, reportage photographer. “It’s a sort of dating of my work.

There was the period of the grain, more or less acceptable, and then the arrival of the pixel. Digital tools have their good qualities and their defects. You can’t make a photo today like you would with a film camera. And when you use digital to create images in the manner of film, you make a severe mistake, in my opinion.

Just like video in its early days, in the face of 35mm, with its images that lacked precision and offered a particular texture, digital has its assets–and it is precisely these that must be played with rather than attempting to imitate what has already been produced. And then there is a point that seems essential to me: digital invites a profusion of images, so one takes less care of one’s shots. Globally, if I analyse my work between film and digital, I notice that the number of good photos on a reportage are less numerous in digital than with my old film camera. This gives me food for thought.

As you can see, there is a lot of balance between the two. Digital has immensely popularised photography and has made the work of talented photographers known through social networks and the incredible apps that exist on the market.

For the nostalgic, modern digital apps offer photographic renderings of legendary cameras: Instamatic and Polaroid are now offered by the Hipstamatic app. Faded colours and frayed outlines tend towards overexposure, but let’s not fool ourselves; we are talking about vintage texture, not the concept of the instant photo.

When digital technology helps to delve into the past: 3D printing

And if some photographers, weary of digital, want to go back to the roots of photography, digital also offers a way back in time. Traditional 3D printing, FDM (Fused Deposition Modeling) technology, is used to reproduce many accessories, but the offer is less efficient on the camera side.

The most reproducible models are the pinhole camera (remember the camera and hole in the window exercise). The pixelvalley.com website offers you a digital pinhole camera you can make yourself!

As for real cameras, there are two innovations: the Open Reflex by Léo Marius, an open-source camera compatible with Nikon lenses but which only offers a single aperture at 1/60 s, and the SLO, created by Amos Dudley, a fixed-focus compact camera in which all the elements (even the lens) are printed in plastic.

In conclusion, from the camera obscura to the camera plastique, photography has come a long way over the years. Yet throughout all the innovations, changes and improvements covered in this dizzying overview, there is one common denominator that will never change and which constitutes the absolute talent of the photographer: your eye.

Whether you are a fan of the camera, still present today, a lover of film or a fan of the new technologies and digital, it is your eye, your vision, that will ultimately create your own memorable images!

We look forward to seeing what you can do!

Photos Credits: Mick Haupt, Kodak Brand